The Tuskegee Institute Study and its Health Impacts Today

Standing outside Orlando Science Center in Loch Haven Park stands the Red Tails Monument — a 12-foot bronze spire leading up to four P-51 Mustang aircrafts in the “missing man” formation. This monument to the “Red Tail Angels” of the Tuskegee Airmen pays tribute to a group of Black pilots who graduated from the Tuskegee Institute.

However, not everything about the Tuskegee Institute is a cause for celebration. In fact, for the 40-year span between 1932 and 1972, the university was home to a horrific experiment whose impacts are still felt even today.

The Tuskegee Experiment, as it is commonly known, sought to study the long-term effects of untreated syphilis, a disease caused by the bacterium Treponema pallidum. Over the course of the investigation, 399 African-American men with latent syphilis (that is to say, they were asymptomatic but had bacteria present in their bodies) were observed, along with 201 healthy men in a control group.

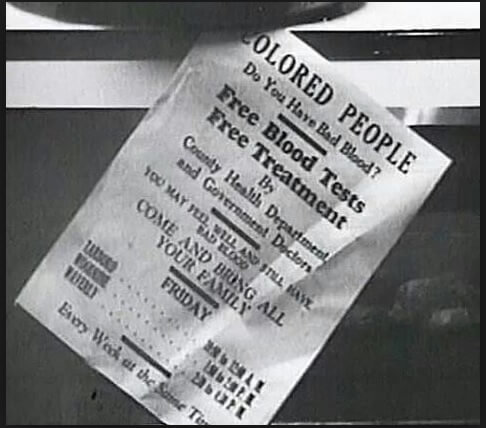

Signs stating “YOU MAY FEEL WELL AND STILL HAVE BAD BLOOD. COME AND BRING ALL YOUR FAMILY” were posted in Macon County, Alabama — the area around the Tuskegee Institute — in the fall of 1932. As you may recall from history class, this was deep in the middle of the Great Depression. Many folks in this part of the country were sharecroppers, tending farmland in exchange for a portion of the food that was grown. With the promise of a free medical exam and a meal to go with it, lots of people understandably took the signs up on their offer.

What the study designers neglected to do was tell participants that they had syphilis. That’s right—in a study of how a disease affects a human long-term, the human participants were never told they had the disease in the first place! Most egregiously, penicillin was a widely-accepted, widely-available standard treatment for syphilis by 1947. The study leaders did not allow the patients enrolled to receive this treatment, instead choosing to allow them to continue to be sick for almost 25 more years. Out of 600 initial participants, only 74 were alive at the time the study ended.

There was public outrage after the story of the Tuskegee experiment came out in 1972. Congress responded to the outcry and passed the National Research Act in 1974. This law mandated that study participants give “informed consent,” meaning they must know what they are being studied for, and that they be given accurate medical information of their diagnoses and test results.

The effect of this eroded trust in medicine persists even now. There are known racial gaps in access to healthcare and enrollment in medical school. Groups such as the Association of Black Cardiologists (ABC) are working to eliminate these differences in access, with the vision that all people—regardless of race, gender, or other characteristics—should equally benefit from known ways to reduce the occurrence of heart disease.

Unfortunately, public trust in health systems was severely shaken by this news, especially among Black Americans. Studies have shown that there was an over 20% reduction in preventive healthcare by older Black men in the area around Tuskegee.

It is important to remember why we honor February as both Black History Month and American Heart Month. Heart disease claims over 650,000 American lives every year. Due to disparities in our healthcare system, this includes a disproportionate number of people of color, including Black Americans.

Educator Resources

If you'd like to learn more about the Tuskegee Institute Syphilis Study or turn this lesson into a lesson for students, check out some of the following educator resources.

- PBS has wonderful resources and lesson plans on the Tuskegee Syphilis Study

for both educators and students: https://florida.pbslearningmedia.org/resource/finding-your-roots-510/tuskegee-study/ - The Association of Black Cardiologists (ABC) published several resources to educate people on heart health: https://abcardio.org/abc-educational-resources/

- Celebrate American Heart Month with fun and engaging activities for all ages: https://www.actionforhealthykids.org/activity/celebrate-heart-health-month/